As discussed a couple of weeks ago in this blog (here), cycling has long been understood as a super-efficient mode of transport. So it is no surprise that in recent years urban planners have turned to bicycle-sharing schemes as they try to enhance sustainability and livability in their cities. According to urban mobility advisor Peter Midgley, “bike sharing has experienced the fastest growth of any mode of transport in the history of the planet”.

These schemes do not rely solely on the awesome efficiency of a human coupled with a bicycle. Rather, they try to integrate bikes and public transport within the framework of a sustainable urban mobility policy. Planners are beginning to realize that for too long urban planning has been held hostage to cars. For instance, the European Commission estimates that over €100 billion is lost every year due to traffic congestion, so there is certainly incentive to smarten up urban mobility.

This graph (produced by Quay Communications Inc.) provides the context of bike sharing in urban mobility:

There are currently around 700 bike share schemes worldwide and many more in the pipeline. But they are not exactly new. The first such scheme started in the 1960s in Amsterdam when an anti-establishment group, intent on saving their city from the blight of the motor-vehicle, placed fifty white bikes in the city for people to use for free. The great idea lasted a matter of days – the bikes were tossed in canals, stolen and confiscated by the police. But the idea caught on and we are currently witnessing something of a renaissance.

The current crop of bike share projects being rolled out – the so called fourth generation – are considerably more sophisticated and are deployed at a much greater scale than early versions. They involve bikes which utilize smartcards and GPS technology and are anything but old clunkers (as their price tags testify).

While clunkers were once the primary mode of transport in China, during the last twenty years bicycle transport has plummeted in China and a series schemes are currently attempting to reverse that decline. The world’s two largest schemes, in Wuhan and Hangzhou, have 160,000 bikes between them but have struggled for patronage despite being provided free of charge by municipal authorities. Maybe the humble idea of the bicycle still involves too much cultural baggage in China.

Perhaps the most high profile bike share example is Paris’ Vélib’ – or “bicycle freedom”. Launched in 2007, Vélib’ now has 24,000 bikes and boasts of 100,000 trips per day. For a nominal annual fee, subscribers are entitled to use the bikes for half hour intervals at no additional cost. Commuter cycling in Paris surged by 45% in Vélib’s first year, and a report from the European Cycling Foundation claims that Vélib’ has now increased cycling rates by 70%. So, not only does Vélib’ complement the ubiquitous Paris metro, but it has also been recognized as a major catalyst for more cycling.

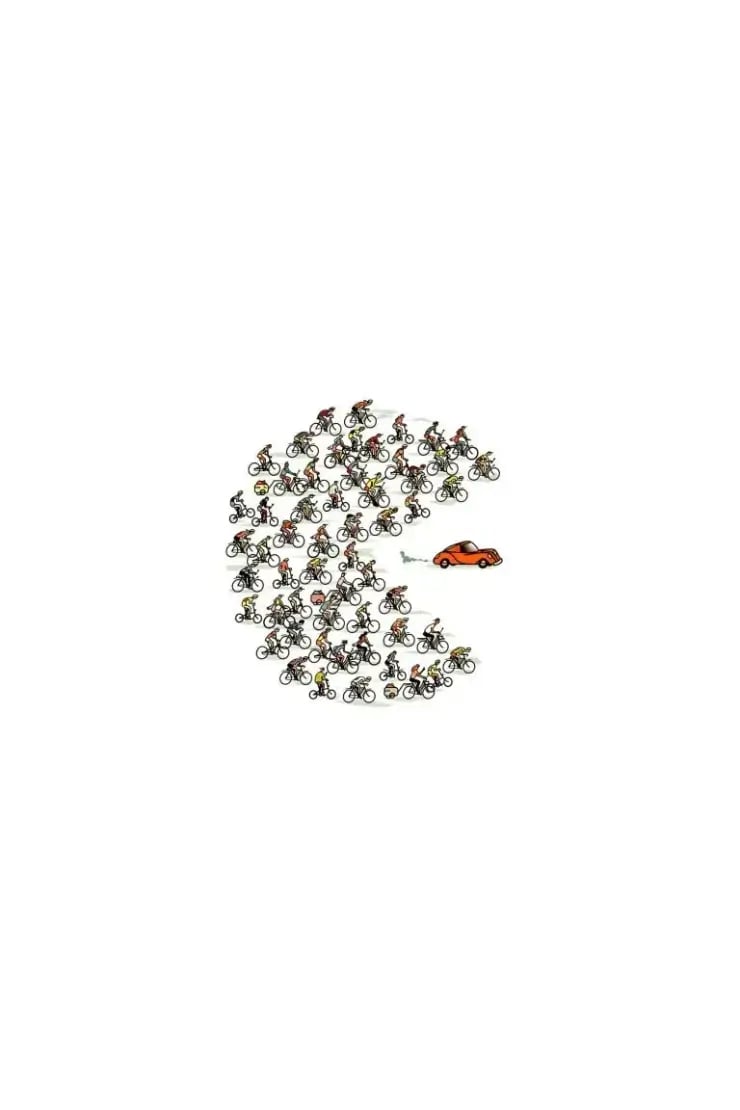

Such ‘positive externalities’ resulting from bike sharing make it difficult to properly quantify the benefit of these schemes leaving them vulnerable to claims that they are a drain on the public purse. But the ‘ultimate goal of bike sharing’ according to Peter Midgley ‘is to expand and integrate cycling into transportation systems, so that it can more readily become a daily transportation mode’[1]. As a critical mass of cyclists develops, and more people become accustomed to the particular benefits of these schemes – convenience, speed and low costs – they also are likely to see the virtues of cycling more generally. This makes the political task of introducing more cycling infrastructure that much easier, spurring something akin to a “virtuous cycle”.

[1] See the background paper on bicycle-sharing schemes that he prepared for the UN here.

Article image by Christoph Hitz.