Ever since the 1980s, during the early years of the environmental movement, there has been a call to abolish harmful subsidies. Technologies and industries harming the environment should no longer be funded by the public was the message. In the course of the last 20 years, especially since the 1990 Rio summit, this call has received more and more attention from the political mainstream, culminating in 2006 in an official policy against environmentally harmful subsidies (EHS) called the European Sustainable Development Strategy. But what is the “H” in EHS? And why are the subsidies harmful? In which ways is money shifted from taxpayers to polluting industries? How do EHS facilitate negative behavior towards the environment? What is the total cost of EHS, for the economy as well as for the environment? Find answers to these questions in this article.

So was 2006 an unprecedented summit of public EHS awareness? Certainly not since it is a rather old story. But 2006 was the year when getting rid of EHS was put on the political agenda at an unprecedentedly high level, in unprecedentedly drastic words:

The European Commission has been called upon by the EU Sustainable Development Strategy (2006) to draft a roadmap for the reform of EHS, sector by sector, with a view to gradually eliminating them.

(Environmentally Harmful Subsidies: Identification and Assessment, by the Institute for European Environmental Policy, a report from november 2009)

What Exactly are Environmentally Harmful Subsidies?

Wasteful government spending comes in many different forms. The most obvious are direct spending on discretionary programs and mandatory programs such as commodity crop payments. Slightly less transparent are tax expenditures, privileges written into the tax code, or below market giveaways of government resources like timber and hardrock minerals. Even more opaque is preferential government financing for harmful projects through bonding loans, long term contracting authority and loan guarantees, and risk reduction through government insurance and liability caps.

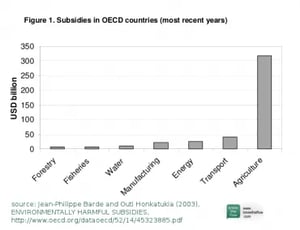

The Green Scissors 2011 report, from which I have taken this paragraph, lists all environmentally harmful subsidies (EHS) in the US, every single one of them. The initiative that published the report describes itself as consisting of a “diverse coalition of environmental, taxpayer, free market and consumer groups”. According to its report, the EHS total in the USA is an incredible 380 billion dollars a year. OECD estimates are more modest, calculating 400 billion USD annually for all OECD countries (see report below).

However, saving the taxpayer useless expenses is certainly an honorable action, but not the most important reason for a drastic reduction of environmentally harmful subsidies.

The downside of all kinds of subsidies, as reviewed in a 2003 publication by two highly placed OECD officials, Jean-Philippe Barde and Outi Honkatukia, are numerous:

Subsidies distort prices, affect resource allocation decisions and change the amount of goods or services produced and consumed in an economy. Policies providing subsidies are generally introduced for various social or economic reasons, but they can have unintended negative effects on the environment that are generally ignored.

Reasons for EHS

In regard to all the downsides, why were the subsidies introduced in the first place? The above mentioned report also specifies “various social or economic reasons”.

Support measures are put in place to enhance the competitiveness of certain products, processes, industries, or develop the employment and income of social groups or regions. In general, the full economic, financial, environmental and social costs of support measures are not considered, and on balance these costs may often outweigh the benefits of implementing the support measure, thus leading to significant government intervention failures.

Good Subsidies Useless Unless We Stop Bad Ones

The negative picture we get when it comes to markets being influenced by the state is not surprising – our sources were “free market” supporters, tax payer union opinions, such as those from Green Scissors, and a governmental institution, namely the OECD. On the other hand, environmental NGOs and natural scientists usually call for a stronger state in order to protect interests in nature. They are joined by a rising share of economists and policy makers who have realized that we need to think beyond the oil era. Saving the economy, in the long run, is only possible through a change of paradigm leading towards sustainable development. Government incentives such as pricing carbon emissions, as well as support for green investments, are only two of the changes needed. Running a low-carbon business, and supporting its development politically, is the key to change.

However, if the environmentally harmful subsidies continue to exist, the “good“ incentives will be counterbalanced by the bad ones:

Not all subsidies are bad for the environment. (…) Some subsidies are used to support the generation of environmental benefits. (…) However, all of these subsidies are higher than would otherwise be needed, in so far as they are used to offset the environmental damage caused by other policies that stimulate environmentally harmful production, and many are not well targeted to achieve specific environmental outcomes.

So wrote Barde and Honkatukia in the report we’re already familiar with. Personally, I have to add that rather than supporting individual technologies, it would make more sense to change the structural conditions. To illustrate this, let’s take the transport sector as an example. Buying a hybrid car is better than buying a conventional one, but instead of subsidizing cars, we should make public transport, walking and cycling more attractive since this is not only much more energy-efficient and beneficial for society, but also most cost-effective. Increasing fuel prices, a measure that would influence overall economic conditions, would facilitate a shift to climate-friendly mobility in a much more effective way than incentives to buy hybrid cars.

Agriculture Biggest Recipient of EHS

Apart from transport (for instance, motor vehicles are indirectly subsidized in most countries through free public streets and parking), the sector most entangled in subsidies harming the environment is agriculture. The following graphic from 2003 shows how EHS are massively applied this sector:

Biodiversity reduction through vast monocultures and sponsored pesticides, eutrophication of water bodies due to massive use of fertilizers, overproduction – the list of negative effects caused by agricultural subsidies is endless. Not only on land, but also offshore: European, American and Japanese fish trawlers have reduced the global marine livestock drastically – with the help of official subsidies.

Transport, agriculture, fisheries. Three fields strongly affected by EHS. A fourth one, not least important, is energy. Barde and Honkatukia:

Fuel tax rebates, subsidies for road transport, and low energy prices generally stimulate the consumption of fossil fuels and greenhouse gas emissions and increase congestion and air pollution.

By Cancelling EHS, 6% GHG Reduction Possible in Developing World

OECD’s Outlook to 2050 (the findings of which were summarized in a recent article on knowtheflow) makes clear that not only developed, but also developing countries affect the climate through harmful subsidies:

OECD Outlook simulation shows that phasing out fossil fuels subsidies in developing countries could reduce by 6% global energy-related GHG emissions, provide incentives for increased energy efficiency and renewable energy and also increase public finance for climate action.

Solution I: Make Subsidies Transitory

No doubt: something has to change, rather sooner than later. But where should we start? What’s the alternative? And why is there no progress? Two approaches generally come up to resolve the EHS issue. First, when introducing a new subsidy, there should be a limited time span for its validity:

Subsidies are at the core of the sustainable development paradigm in a complex and paradoxical manner. On the one hand, while it is largely recognised that sustainable development implies, inter alia, well functioning and non distorted markets, subsidies constitute a prominent form of market distortion; on the other hand, support measures may be needed to start a virtuous cycle of sustainable development, for instance to help certain economic sectors or regions; such measures should be transitory with a firm sunset clause.

(Barde and Honkatukia, 2003)

Solution II: Cut Subsidies, Internalize Costs

Second, instead of a focus on subsidizing good practice, governments should address structural conditions so that external costs are internalized.

The need for an effective internalisation of externalities, which economists have been promoting for several decades, is now increasingly recognised by policy makers. Although the “Polluter-pays Principle” was promulgated thirty years ago by the OECD (1972), the implementation of an economic discipline and rationale in environmental policy is fairly recent and far from fully achieved.

(Barde and Honkatukia, 2003)

Reasons Behind Inaction

Why does nothing happen? Why do EHS continue to result in pollution? Apart from the obvious – the interests and lobbying of particular industries – the Institute for European Environmental Policy identifies a lack of clear definition and methodology in their report from November 2009:

The importance of the review and potential reform of environmentally harmful subsidies (EHS) is well recognised and increasing policy support has been given to underline that progress is needed (…). While there have been some successes in the reform of EHS, there has been much less reform than could have been expected from simply looking at the environmental damage these subsidies cause and the potential global economic savings possible by reform.

While the main barrier to the reform of harmful subsidies has arguably been the resistance by vested interests and associated difficulty of gaining political support to push difficult changes, the review and reform of subsidies has also been hindered by: the lack of an agreed definition of subsidies, of agreed methods to keep track and quantify them, the lack of application of assessment methods and a lack of commitment to keeping a transparent inventory of subsidies.

The institute, in 190 pages, resolves these problems. In “Environmentally Harmful Subsidies: Identification and Assessment“, a clear methodology is proposed, and a clear definition of EHS is given. Alas: no reason left for keeping any of the EHS!

Further Reading

- Friends of the Earth, Public Citizen, Taxpayers for Common Sense, The Heartland Institute (2011): Green Scissors 2011

- Jean-Philippe Barde and Outi Honkatukia (2003) , ENVIRONMENTALLY HARMFUL SUBSIDIES, contribution to the ERE 2003 yearbook

- Stop Subsidies Polluting the World – Recommendations for Phasing-out and Redesigning Environmentally Harmful Subsidies (2004), Publication by the European Environmental Bureau with the assistance of its Working Group on Environmental Fiscal Reform

- Valsecchi C., ten Brink P., Bassi S., Withana S., Lewis M., Best A., Oosterhuis F., Dias Soares C., Rogers-Ganter H., Kaphengst T. (2009), Environmentally Harmful Subsidies: Identification and Assessment, Final report for the European Commission’s DG Environment, November 2009.

- Pier Carlo Padoan (May 2010), How to correct global imbalances, OECD Observer No 279

Article image by Moritz Buehner, combining Andrew Stawarz’s digger with Jake Wasdin’s coins.