The ISO 14000 series has proved to be handy for quite a while now. Companies and public institutions have valued the universal guidelines for all sorts of environmental management procedures – energy management, carbon footprinting and life cycle assessment, to name the most important ones. Two years ago, a new seed was planted in the ISO 14000 orchard, bearing the name ISO 14051. This new norm was equipped with the powerful claim of combining the material and energy efficiency improvements already known from the other norms with measures to increase cost efficiency as well. In order to match these expectations, the principle that ISO 14051 relies on is called Material Flow Cost Accounting (MFCA). Despite its apparent “double” usefulness – never has it been more obvious how ecologic and economic benefits go hand in hand – the new norm has not yet caught up with the popularity of its brothers and sisters. In an attempt to help in paving the way to an increased number of 14051 certified companies, those willing to both reduce their financial costs and their environmental burden, let me explain in simple terms how the 14051 procedure works.

Plan-Do-Check-Act

The basic structure underlying the norm is a simple Plan-Do-Check-Act-cycle (PDCA). However, at first sight, the steps involved in each step of this cycle may be irritating. Among the ten steps, there are lots of different involvements, determinations, identifications and quantifications to set up, mixed with interpretations and communications. Thank god I’m not the first to go through this, thank god some practitioners have already shared their experience, and thank god they have related it to a concrete example! There is a work group called eniPROD that dealt with “Energy-related [technological] and economic evaluation”. Its four researchers – Schmidt, Hache, Herold and Götze – (Germany, correct!) work at Chemnitz University of Technology and they published an extensive, 17-page guide to Material Flow Cost Accounting that can be found in the publicly available “Proceedings” of their first two workshops. The complete proceedings are available for download at the Quality Content of Saxony pages; the MFCA-chapter is number 2-05 (PDF). This document explains the calculation of material flow costs with the help of an example. The example consists of a machine’s manufacture, a machine called an extrusion recipient. Each of its three components goes through four production steps before they’re all joined together by shrink fitting. Once manufactured and sold, extrusion recipients are used to make profiles from raw aluminum billets, e.g. in the automobile industry.

1. Plan: Who? What? When?

The most intuitive part of Material Flow Cost Accounting is probably the planning phase. The ISO norm suggests that you start by involving the company’s management and continue by determining whether your staff is suitably qualified and fully accepts being involved. This is most certainly a wise procedure with whatever planning you have going on; our norm calls it determination of necessary expertise. Step 3 in the planning phase sets the pace for all the other steps, since this is the time when you specify a system boundary and a time period. In other words, how detailed should the accounting become? The researchers from Chemnitz elaborate:

Basically, the boundaries can span a single or several process(es), the whole organisation or even entire supply chains.

The last step in the Plan phase consists of defining what are called quantity centers. What’s that? Different interpretations are mentioned, reaching from the vague, “any potentially loss-causing point”, to the precise processes of “receiving, cutting, assembling, heating and packing”. But really, defining quantity centers means getting a good sketch of what’s happening throughout your production.

2. Do: Model Material and Financial Flows

Having the quantity center sketch as a basis, you can easily discover the in- and outputs for each process. This first step in the Do-phase, and the fifth step overall, is called identification of inputs and outputs for each quantity center. Next, these throughputs need to get a physical unit for quantification. This quantification refines inputs and outputs, making it possible to see material flows. Ah, right: because the method we’re dealing with is a cost accounting one, not only do we need a physical unit, but also a financial one. It’s as simple as that: steps six and seven deal with quantification of the material flows in physical and monetary units.

In order to accomplish these steps, you can either hire a busload of mathematically fit day laborers, or apply a neat computer model. The Chemnitz-researchers preferred the latter. Their choice was the material flow management and LCA software Umberto. Before we jump right into praxis, and looking at some screenshots, let me quote one of the authors’ introductory sentences that recapitulates the initial reason for choosing MFCA, or why anyone would want to model their production process using a computer program.

A precondition for enhancing material efficiency is a high transparency of material flows within or even across companies and the corresponding material costs.

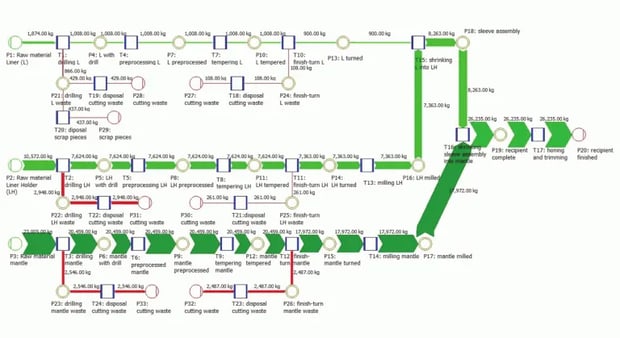

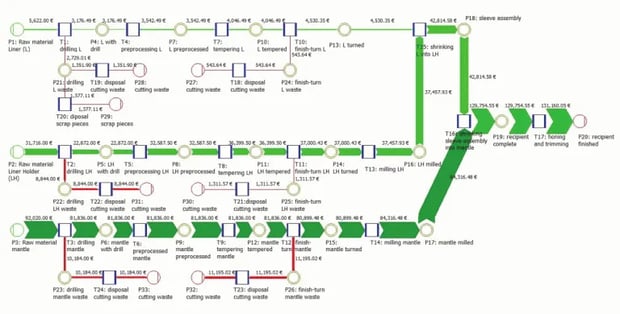

Yes, that’s why. Because with this understanding at hand, it is just a question of time before material and energy efficiency increase. Qualified day laborers are a thing of the past anyway… So for the detailed procedure of how to set up this flow cost model in Umberto, see pages 10 and 11 of Schmidt, Hache, Herold and Götze’s PDF. So where are the screenshots? Here:

And here:

3. Check: Interpret + Communicate Results

Phase three has two steps that are a logical consequence of creating the model in the previous phase. In step 8, data summary and interpretation, the necessary conclusions are drawn from the material flow models. In step 9, these results are communicated. On page 12 of their paper, Schmidt et al. explain how comparison of the two flow models, the material one and the monetary one, leads to unexpected discoveries:

The comparison […] shows differences between the relative quantities and costs of product and loss flows. For example, the incoming and the outgoing arrow in T5 have the same width in figure 3, based on the assumption that there are no quantity differences. In figure 5, the outgoing arrow is wider than the incoming arrow because of added system costs. As a second example, it can be seen that cutting waste in P28 is less cost-intensive than cutting waste in P27. The relation of quantities in figure 3 is nearly 4:1 while the relation of costs in figure 5 is approximately 2.5:1. This can be explained by the increasing value of materials within material flows.

Material Flow Cost Accounting is not limited to manufacturing. On its corresponding website, the international standards organization makes this point:

Under MFCA, the flows and stocks of materials within an organization are traced and quantified in physical units (e.g. mass, volume) and the costs associated with those material flows are also evaluated. The resulting information can act as a motivator for organizations and managers to seek opportunities to simultaneously generate financial benefits and reduce adverse environmental impacts. MFCA is applicable to any organization that uses materials and energy, regardless of their products, services, size, structure, location, and existing management and accounting systems.

4. Act: Improve!

The final MFCA step, identification and assessment of improvement opportunities, is up to you. Happy Flowing and fruitful Accounting!

Further Reading

Schmidt, A., Hache, B., Herold, F., Götze, U. (2013): Material Flow Cost Accounting with Umberto®; Proceedings of the 1st and 2nd workshop of the cross-sectional group 1 “Energy-related technologic and economic evaluation” of the Cluster of Excellence eniPROD (231-247), Collaborative Research Centre 692, Chemnitz University of Technology. PDF downloads here.

Article image shot and edited by Moritz Bühner, CC BY 3.0.