The EU Waste Framework Directive (WFD) is a cornerstone of EU legislation, shaping waste management and sustainability practices across the region....

EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR): Obligations, Risks & Compliance for Producers

Deforestation and forest degradation linked to agricultural production and global commodity trade have become major regulatory concerns worldwide. To...

Understanding the 5 Life Cycle Stages of a Product in LCA

Life cycle thinking has become indispensable for companies navigating the EU's expanding sustainability regulations. Understanding the 5 product life...

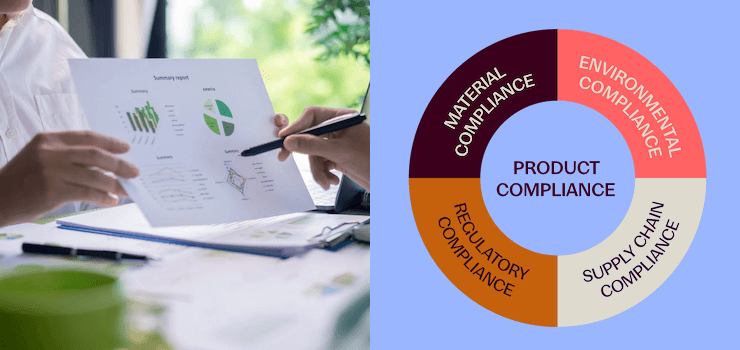

Product Compliance Made Simple: Reduce Risk, Ensure Market Access

Product compliance is now a critical factor for companies working with chemical substances in the United States or the European Union. Regulations...

Mastering SVHC Compliance: A Business Guide to Substances of Very High Concern

Substances of Very High Concern (SVHCs) remain a critical compliance challenge for companies operating in the European Union. With the REACH...

IPOINT

Latest News

The EU Waste Framework Directive (WFD) is a cornerstone of EU legislation, shaping waste management and sustainability practices across the region....

EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR): Obligations, Risks & Compliance for Producers

Deforestation and forest degradation linked to agricultural production and global commodity trade have become major regulatory concerns worldwide. To...

Understanding the 5 Life Cycle Stages of a Product in LCA

Life cycle thinking has become indispensable for companies navigating the EU's expanding sustainability regulations. Understanding the 5 product life...

Product Compliance Made Simple: Reduce Risk, Ensure Market Access

Product compliance is now a critical factor for companies working with chemical substances in the United States or the European Union. Regulations...

Mastering SVHC Compliance: A Business Guide to Substances of Very High Concern

Substances of Very High Concern (SVHCs) remain a critical compliance challenge for companies operating in the European Union. With the REACH...

TSCA Compliance Regulation Guide: Navigating Chemical Reporting for Your Business

TSCA compliance is gaining urgency. With rising enforcement and evolving reporting requirements, the Toxic Substances Control Act is reshaping how...

EU Battery Regulation: New Requirements Across the Life Cycle

Whether in electric vehicles, industrial machinery, or consumer electronics, batteries are at the heart of today’s manufacturing value chains. For...

End-of-Life Vehicles (ELV) Directive: Key Facts for ELV Compliance

The End-of-Life Vehicles Directive (ELV Directive) is a core regulation in the European Union – designed to reduce the environmental impact of...

Circular Business Models: How Companies Create Value in a Circular Economy

For decades, most companies have operated under a linear economic model: extract resources, manufacture products, sell them, and dispose of them...

Circular Economy Action Plan: How the EU Green Deal Is Transforming Europe’s Economy

The Circular Economy Action Plan (CEAP) is a core pillar of the EU Green Deal. Adopted by the European Commission in March 2020, it defines Europe's...

Dodd-Frank Act Section 1502: Conflict Minerals & SEC Reporting Requirements

The Dodd-Frank Act may have been signed in 2010, but Section 1502 on conflict minerals remains a critical compliance challenge for manufacturers...

Conflict Minerals Explained: Understanding 3TG and Their Compliance Impact

Conflict minerals – tin, tungsten, tantalum, and gold (3TG) – are essential raw materials in countless modern products, from smartphones to cars and...

EU Conflict Minerals Regulation: A Compliance Imperative for Global Supply Chains

Armed conflicts and human rights abuses linked to mineral sourcing have long raised red flags. With the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation in force,...

REACH Regulation & Reporting: Navigating EU Chemicals Compliance with Confidence

A single screw coated with a restricted substance can trigger penalties across 30 countries – that’s today’s reality for manufacturers. Since 2007...

China Automotive Material Data System (CAMDS): What Automotive Companies Need to Know

The China Automotive Material Data System (CAMDS) is a regulatory data platform used in the Chinese automotive industry to collect information about...

What Is IMDS? A Practical Guide for Automotive Suppliers

The International Material Data System (IMDS) is the global standard for exchanging material data in the automotive industry. OEMs worldwide require...

CSRD & Scope 3: Why Value Chain Emissions Demand a Closer Look

Understanding Scope 3 emissions is no longer optional – it’s a regulatory imperative. Under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD),...

Responsible Minerals: Sourcing Policy and Use in Global Supply Chains

If you manage supply chain compliance, you know the landscape has dramatically shifted. What began as conflict minerals reporting focused on 3TG...

Sustainable Product Design: Driving the Future of Responsible Manufacturing

Sustainable product design is more than just a trend; it is a necessity in today’s industrial landscape. As businesses strive to minimize their...

Navigating Automotive Regulatory Compliance in a Complex Industry

In today’s automotive industry, compliance is a strategic necessity. From hazardous substance restrictions to end-of-life vehicle directives,...

CSRD & Omnibus Proposal 2025: Key Changes, New Timeline & Impact for Your Business

On February 26, 2025, the European Commission published the long-anticipated Simplification Omnibus proposal. This legislative package forms part of...

Sustainable Manufacturing: How to Achieve a Green Production

Industrial engineering and manufacturing of products is always accompanied by the extraction and consumption of raw materials from nature and the use...

Eco Efficiency Analysis: Balancing Profit and Planet

In today's business landscape, companies face the dual challenge of achieving profitability while minimizing their environmental impact. This article...

Combining Product Compliance & Sustainability: A Must for Modern Businesses

Businesses today are no longer grappling with just product compliance or sustainability in isolation. These two dimensions are converging, driven by...

The Digital Product Passport: Regulation, Requirements, and Industry Impact in the EU

The Digital Product Passport (DPP) is one of the European Union’s most ambitious initiatives to promote transparency, traceability, and sustainable...

E-Waste Dilemma: The Environmental Impact of Electronics

In today's world, electronic devices are indispensable. However, their production, use, and disposal have significant environmental impacts. The...

Navigating New Regulatory Waters: The Imperative of Balancing Human Expertise and Technological Innovation

As sustainability transitions from being a goal to an essential requirement in the automotive industry, grasping the current trends is vital. Our...

What is Resource & Material Efficiency for Businesses?

Resource efficiency stands for the relationship between natural raw materials or technical-economic materials and the benefits gained from their use,...

Shifting Gears for a Sustainable Future: A Financial Commitment to Compliance and Eco-Friendly Practices

Our annual Automotive Trend Survey captures the insights of compliance and sustainability experts from across the industry and reveals four key...

Prioritizing a Green Future: Sustainability Surpasses Compliance

In an era where sustainability is not just a goal but is becoming a mandate for the automotive industry, understanding the landscape is vital....

Over 50% See Growing Interest in Sustainability

The automotive sector is undergoing a significant transformation, with sustainability taking center stage. The latest iPoint Automotive Compliance &...

PFAS Regulation in the EU: From POP to REACH

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have gained global attention due to their widespread use and potential effects on human health and the...

Powering the Future: Sustainability in the Electronics Industry

In an era where electronic devices seamlessly integrate into every facet of our daily lives, the demand for sustainability in the global electronics...

EPA's New PFAS Reporting Rule Under TSCA - Covered by our Latest Rule Group

In the rapidly evolving landscape of environmental regulation, the challenge of managing Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) has become a...

Deciphering the Carbon Footprint of Car Manufacturing

According to a report by the European Environment Agency, transport was responsible for around a quarter of the EU's total CO₂ emissions in 2022....

From Tailpipe to AI: A Brief History of LCA in Automotive

To all the LCA enthusiasts and sustainability experts out there -– this one is for you. Let's take a short ride down memory lane, looking at the...

Sustainability in the Automotive Industry: Navigating the Green Road

When it comes to sustainability, all eyes are on the transport sector and the automotive industry in particular. The accelerating concern for climate...

LCA Data for Life Cycle Assessment: Unlocking Environmental Insights

In the pursuit of sustainability, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a powerful tool for evaluating the environmental impact of products,...

Understanding PFAS: Regulations & Relevance for Companies

PFAS, or Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, have become a significant global concern due to their prevalence and potential health and environmental...

What challenges arise in the adoption of circular economy?

There is a wide range of potential benefits, clearer regulations, policies, as well as urgency (see article "How companies benefit from circular...

Integration of the Catena-X PCF Rulebook into IMDS

The Catena-X automotive network has achieved a significant milestone in standardizing the requirements for CO2 footprints in the automotive industry...

Are there barriers to CO2 reduction in the automotive industry?

In the iPoint Sustainability & Compliance Trend Study 2022, we have gained many valuable insights. Among other things, our survey showed that 56% of...

Green speed? This is how important sustainability and CO2 reduction targets are for the automotive industry

The world is changing faster than ever before and the automotive industry is at a turning point. At a time when environmental impacts are becoming...

CSRD – Well Prepared Thanks to Data-Driven Intelligence

Sustainability in Discrete Manufacturing: Capture, Analyse, Report and Optimise. Is sustainability the new compliance? The intent behind the European...

Surprising survey results on compliance and sustainability in the automotive industry

The iPoint Compliance & Sustainability Trend Survey is one of the world's largest surveys offering insights into sustainability and compliance. Of a...

A "Paper Tiger" gets its Teeth

The EU is getting tough: CSRD. The EU is to become climate-neutral by 2050 - to achieve this goal, the "toothless paper tiger NFRD (Non Financial...

Circular Economy: a Key Factor to Sustainability

As we navigate today's global environmental challenges, the circular economy offers a refreshing perspective, showing us how to do more with less. By...

"Companies simply cannot deliver as they want."

"Companies are faced with a major problem: They simply cannot deliver as they want - there are too few LCA experts and the dynamics are too high." -

Building a Digital Circular Economy

In today's rapidly evolving business landscape, the integration of digital technologies is paramount for the successful implementation of Circular...

The iPoint Sustainability and Compliance Trends Survey 2022

Surprisingly, companies worldwide, especially in Asia, increasingly view sustainability and compliance as important factors in their business...

Implementation of digital technologies for a circular economy and sustainability management in the manufacturing sector

Implementation of digital technologies for a circular economy and sustainability management in the manufacturing sector

Understanding the ISO 14000 Family of Standards

Back in the year 1987, the International Organization for Standardization introduced a number of norms known as the ISO 9000 series. For the first...

What is an Environmental Management System? From EMAS to ISO 14001

The term environmental management system refers to a holistic and strategic framework with the introduction of which companies commit themselves to...

How companies benefit from circular economy

Converting a company to a circular economy is an important step but many business leaders aren't sure what the consequences will be. This article...

Implementation of circular economy strategies in product development

Considering aspects of the circular economy right from the product design stage is the most effective approach a company can take to improve the...

How new policies worldwide advance the Circular Economy

The growing importance of the circular economy and circular business models manifests itself in policies and regulations designed to advance the...

How the automotive & electronics industry transitions towards the Circular Economy

In addition to activities of legislative bodies, industry itself has set out on a path towards circular economy, sometimes moving at an even faster...

Drive business value by data analysis – iPoint CARE

Data analysis for product compliance and sustainability, like Life Cycle Assessment or Product Carbon Footprints, provide your company with a crucial...

Digital Product Passports: Pioneers for Sustainable Economy

Whether climate protection, circular economy, or resource efficiency, without transparent value and supply chains, many political targets and goals...

Digital technologies for sustainable product management in a circular economy

The increased use of digital technologies is considered as a key enabler for a more sustainable and circular economy. A recent study by the Christian...

Digital Battery Passports to Enable Circular Battery Ecosystems in the EU

The industry-driven debate on digital battery passports as enablers of a circular economy has gained increased momentum. To provide a research-guided...

Collect Data for Compliance and Sustainability – iPoint CARE

Data collection is the first step on the road to successful product compliance and sustainability in order to obtain type approval and bring a...

Sustainability and Compliance Trends Study

The world’s largest sustainability and compliance trends survey entered its fourth round, with over 1000 responses received from experts across the...

Sustainable Product Development in a Circular Economy

The concept of circular economy is of great interest to companies since it provides a framework to align with the Sustainable Development Goals. So...

To Recycle or Not to Recycle – PVC Cable Waste is the Question

Recycling – it’s the magic word when the ill-informed think “environmental friendliness”. “Recyclable” – the number one green term that doesn’t mean...

The Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation: A Spotlight on Finance

A conversation between Joerg Walden of iPoint and Juan Ibañez and Dr. Chris Bayer of Development International e.V.

Circular Economy Implementation in Businesses – Cross-sectoral findings

by Lukas Stumpf, Josef-Peter Schöggl, Rupert J. Baumgartner

Sustainability and Compliance Trends 2020 With a Focus on the Automotive Industry

The pandemic crisis heavily influenced the year 2020, which likely also impacted iPoint’s Trends Study 2020. However, in addition to the sudden...

Discover the iPoint Suite

The iPoint Suite offers solutions for the entire product life cycle – from design to production and use to recycling and reuse.

Duty of Care Also in Germany: The Impending Mandatory Due Diligence Legislation

At the beginning of March, German ministries published the government draft of a mandatory supply chain due diligence law...

How sustainable is the Circular Economy?

Josef-Peter Schöggl, Lukas Stumpf, Rupert J. Baumgartner

ECHA SCIP Database Explained: From REACH to WFD

The ECHA SCIP database increases transparency on hazardous substances in products. Under the EU Waste Framework Directive SCIP rules and in line with...

CO2-pricing in Germany – Significance and consequences for companies

Since January 1rst, 2021, in Germany a new CO2 pricing on fuels has been in force. It demands that from now on, a distributor will have to pay a...

Carbon Transparency – an Opportunity for Companies and the Environment

Reducing carbon emissions is undoubtedly one of the greatest challenges for companies to combat climate change. “Carbon is the new calorie”, says...

Maximizing Products’ Sustainability Performance and Circularity with Digitalization – Update on Research Activities

Anything but a standstill is currently happening in the Christian Doppler Laboratory for Sustainable Product Management: the team of the...

I care, you care, we care: The iPoint CARE principle

Many of our customers say that we’ve simplified the complex processes of digitalizing the lifecycles of products, materials, and supply chain...

From Compliance to Sustainability – The iPoint Suite

iPoint’s software covers a lot of ground. In combination, our software products provide a broad spectrum of compliance, sustainability, and risk...

Expanding compliance processes and tools to better manage sustainability

Many companies voluntarily go beyond regulatory requirements, setting higher expectations and standards supporting sustainability initiatives. Many...

End-to-end material lifecycle management is key

When it comes to materials in products, what we call “end of life” is also the “beginning-of-life”. This idea isn’t new, but only around 20 years ago...

A Natural Path to Managing Material Lifecycles

Meeting all local and global regulatory requirements is a must for all companies doing business in the 21st century. Consequently, a robust material...

The current state of material compliance management

Materials and substances used in manufacturing plants need to comply with health, safety, and environmental regulations surveilled by authorities...

Cobalt unmasked – Is cobalt really a sustainable option?

In recent years, the demand for cobalt has steadily increased with the development of the electric vehicle market and the digitalized industry. But...

Compliance Reporting for Electronics – new challenges driven by the Automotive industry and the EU SCIP database

Chemical compliance reporting for electronics or products with electronics in them involves providing detailed substance and materials information...

The new EU Regulation of Medical Devices – MDR

Is your company and your supply chain ready to tackle the new EU MDR requirements? Get prepared for the 7 major changes in Medical Device Regulation.

How The Automotive Sector Can Do MedTech

Due to COVID-19, protective masks and respiratory equipment are in high demand. iPoint Compliance can support the automotive sector in achieving...

Are menstrual cups a “green lie”?

An LCA comparing menstrual cups and tampons shows that products advertised as particularly sustainable are not always the truly sustainable...

The Global Medical Device Industry – a spotlight on India and China

Japan has one of the highest geriatric populations in the world and because of that they have a strong demand for medical devices. They’re one of the...

Medical Device Industry – Trends in 2020

Several global companies from the Medical Device industry like Becton Dickinson, Roche, Emerson or Zimmer Biomet are longterm customers of iPoint and...

How to provide Life Cycle Information for non-LCA experts

Thanks to automatization and data interfacing, LCA is becoming accessible to any role in an organization. Also non-LCA experts can use life cycle...

How to collect information from your supply chain – Where an industry standard does not exist!

When it comes to collecting information from your supply chain, having certain industry standards, such as the Conflict Minerals Reporting Template...

Why we built the iPoint Suite

In iPoint’s software solutions, the CARE principle forms the foundation. All our software solutions collect, analyze, report and help companies to...

Why we CARE – and YOU CARE ALREADY

Since 2001 customers, ranging from SMEs to Fortune 500 companies, have been using our software solutions to CARE ….

Why increasing market dynamics lead to complexity

Today’s companies face high pressure by investors to improve revenue, by regulations to abide by the new rules and by competitors to be ever...

Carbon Footprint of Electric Cars: Is E-Mobility Truly Sustainable?

Electric cars and e-mobility are hotly debated issue right now, both in scientific circles and in the media. Some herald it as enabling mobility with...

Do LCAs reveal green lies?

As life cycle experts know, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a useful tool to either confirm or disprove a product’s assumed environmental advantage....

Cobalt Reporting via the iPoint SustainHub

Cobalt is the key element used in batteries of mobile phones, laptops, and electric vehicles and hence the demand for cobalt has been increasing year...

How to build a sustainable car?

What are the challenges for the implementation of Sustainable Product Development in the automotive industry?

LCA of lithium-ion batteries – there’s more to it than you think

With the use of electric vehicles on the rise, there’s a lot of buzz about how environmentally friendly they are. While operational impacts are low...

Will there be a UK REACH?

What will be the challenges Brexit will have to your business on the products and services that you supply? Will there be a UK REACH for the...

The Sustainability & Compliance Trends Survey 2019

The overwhelming response on our Sustainability & Compliance Trends Survey 2018 encouraged us to continue our research to keep our fingers on the...

Customized Transparency with iPCA Web

The new web-client of the iPoint Compliance Agent, iPCA Web, enables companies to advance transparency in their supply chain and provide their...

Sustainability and Compliance Trends – What Kept Companies Busy in 2018?

At the beginning of 2018, iPoint started to conduct a survey on Sustainability and Compliance Trends 2018 – and the response was overwhelming: More...

SustainHub Roadmap 2019

Free Webinar: Innovative insights and an exclusive outlook on the SustainHub Join Sebastian Dehlinger, Product Manager of SustainHub, on Dec. 5th in...

France’s Due Diligence Law – Loi sur le devoir de vigilance

On April 24, 2013, more than 1,000 people in Bangladesh lost their lives when the textiles factory they worked at collapsed. At that time, a number...

Blockchain for Circular Supply Chain

Blockchain technology enables us to digitize and streamline the supply chain workflows to improve efficiency, reduce costs and improve management of...

New standard ISO 50001 for energy management places increased demands on companies

Recertification of an energy management system according to ISO 50001 has become more demanding – or why a requirement in the accreditation standard...

Life Cycle Impact Assessment – the Most Widely Used LCIA Methods

Whenever someone starts his or her first LCA study, one of the questions to be answered is, which of the available LCIA methods should be used? There...

Human Trafficking and Modern Slavery – how to mitigate financial and reputational risk

According the latest Global Slavery Index (GSI), released in July 2018, it can be estimated that were 40.3 million victims of modern slavery and...

The new California Proposition 65 Warning Regulations

The California Proposition 65 is a California Law that came into effect in 1986.

Welcome to the iPoint Blog!

We are delighted to present you with news and information on the topics and solutions of the iPoint Group.

Innovation@iPoint

The objective of innovation management is to turn great ideas into financially successful products or services. This process used to take place...

Twenty Years in the Making: a Review the 20th Umberto User Workshop

A 20th anniversary is often a marked event, so it was fitting that this year’s Umberto User Workshop was held in Heidelberg, the same venue as the...

Social Life Cycle Analysis: Why Does It Lurk In the Shadow of Environmental LCA?

The term “Life Cycle Analysis” (LCA) is largely assumed to be the technique used for the assessment of the total environmental impact associated with...

Interview with Victor Vladimirov: Hobas Engineering

Gathering quality data is one of the biggest challenges in producing accurate LCAs. In an interview with Victor Vladimirov, environment and energy...

Obtain LCA data from suppliers – Insights from a sustainability consultant

Rebecca LeBlanc is a sustainability consultant at “Strategic Sustainability Consulting” in Boston, USA. Her experience shows that giving the context...

How Traditional Cost Accounting Methods Resolve Carbon Footprint Issues

Life cycle assessment (LCA), in simplified definition, is a task that uncovers all environmental effects a process or a product creates. It is a...

iPoint Joins UN Global Compact

On August 7, 2017, iPoint was officially welcomed as a participant of the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). Launched in 2000, the UNGC has become...

The new CSR Reporting Directive of the EU

Starting with the fiscal year 2017, large listed entities with more than 500 employees will have to disclose relevant non-financial information on...

Innovation Awards for iPoint

In May 2017, independent research firm Verdantix recognized iPoint’s customer Emerson with an Environment, Health & Safety (EH&S) Innovation Award....

Digital Circular Economy – The Digital Revolution of the Circular Economy

In contrast to the linear economy (take, make, use, dispose), the circular economy approach does not see an absolute end to a product or process....

The Life Cycle Perspective in the New ISO 14001:2015 Standard

Following publication of the environmental management standard ISO 14001:2015 on September 15, 2015, the transition period for replacing the old ISO...

Monetary Valuation of Environmental Impacts: The Path to True Cost Accounting

Managing to engage decision-makers at all levels of a company on sustainability matters is an all too common challenge for experts trying to improve...

Material Flow Cost Accounting: Resource Efficiency Made Simple

Many organisations are coming under increasing pressure to minimise the environmental impact of their activities, as well as optimising resource...

Unburnable Carbon: Bill McKibben’s frightening math

An article by veteran American environmental campaigner Bill McKibben appearing in Rolling Stone a couple of years ago framed the issue of dealing...

Long-Distance, Low-Impact? Inside Cargo Ship Travelling

As I sail through the English Channel and complete my last miles around the world on a reefer vessel, accompanying 5000 tons of kiwifruit on their...

From Green to Blue to Gray to Black: The Chromatics of Water Footprints

Because water is the most vital element for life, many contemporary intellectuals expect it to be the most conflict-generating resource of the 21st...

Eco-economic Decoupling: How to Measure a Sustainable Growth

What is decoupling? Green Growth, Sustainable Growth, Green Economy – All of these concepts require decoupling. A decoupling, in a nutshell, that...

Avoiding the Relocation of Emissions – How to Face Carbon Leakage

In the course of the last 20 years, some of the more developed countries achieved a remarkable reduction of carbon emissions. However, taking a...

Getting it Straight: the Carbon Footprint of Wine

I bet you know how much carbon dioxide your car emits per kilometer. Maybe you are also well informed about the carbon reduction goals of the country...

Loading the next set of posts...

.png?width=370&height=150&name=EUDR-header(1).png)

.png?width=370&height=150&name=product-compliance-header(2).png)

.png?width=370&height=150&name=svhc-header(1).png)

.png?width=370&height=150&name=tsca-ipoint(1).png)

.png?width=370&height=150&name=eu-battery-regulation-header(1).png)

.png?width=370&height=150&name=elv-directive-header(1).png)

%20(1)%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Green-Deal-Bild-bearbeitet2%20(2)%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.png?width=370&height=150&name=eu-conflict-minerals-regulation-header(1).png)

.png?width=370&height=150&name=camds-header(1).png)

.png?width=370&height=150&name=csrd-scope3-header(1).png)

.jpg?width=370&height=150&name=responsible-minerals-header(1).jpg)

%20(3).png?width=370&height=150&name=iPoint%20Blog%20Image%20Automotive%20Trend%20Study%20(mit%20Nummern)%20(3).png)

%20(2).png?width=370&height=150&name=iPoint%20Blog%20Image%20Automotive%20Trend%20Study%20(mit%20Nummern)%20(2).png)

%20(1).png?width=370&height=150&name=iPoint%20Blog%20Image%20Automotive%20Trend%20Study%20(mit%20Nummern)%20(1).png)

-1.png?width=370&height=150&name=iPoint%20Blog%20Image%20Automotive%20Trend%20Study%20(mit%20Nummern)-1.png)

.jpg?width=370&height=150&name=1920x768_C(1).jpg)

.jpg?width=370&height=150&name=Kopie%20von%20iPoint%20Blog%20Image%201500%20x%20500%20px%20(4).jpg)

.jpg?width=370&height=150&name=Kopie%20von%20iPoint%20Blog%20Image%201500%20x%20500%20px%20(3).jpg)

.jpg?width=370&height=150&name=Kopie%20von%20iPoint%20Blog%20Image%201500%20x%20500%20px%20(1).jpg)

-1.jpg?width=370&height=150&name=Kein%20Titel%20(1500%20%C3%97%20500%20px)-1.jpg)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Bild%20CD%20LAB%201-1%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=iso-14000-familiy-1500x500-1024x%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Bild%201%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=2-2%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Hubspot_Landingpage_1920x775-2%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Blog_CD-Lab_DT-for-SPM_Feature5-2%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Blog_CD-Lab_Digital-Battery-Passport-2%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Collect-Blogarticle_1500-500-2%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Trend-survey-title-image_1500x50%20(2).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=yash-bindra-RaTPEIwuwXw-unsplash%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=20210825_Blog_SFRD-3%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=meagan-carsience-RmERRki7BCw-unsplash-3%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Trends-Survey-Automotive-2020-3%20(1).webp)

-1.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Duty-of-Care-Germany_March21-Nov%20(1)-1.webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=fly-d-oNBlbvQ2jAc-unsplash-3%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Header-Nov-30-2022-12-59-35-9621%20(3).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Carbon-transparency-teaser-3%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=CD-Labor-Update%20(1).webp)

%20(1)-1.webp?width=370&height=150&name=CARE-1024x345%20(1)%20(1)-1.webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Suite2%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=expanding-compliance2-1024x342%20(2)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=from-compliance-to-sustainability-3-new-1500x500-1%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=2020-09_CM-Cobalt-1024x343%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=electronics-wp-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Blume-1024x342%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Lies-vs-True%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=medtec-india-china_1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=medtec_trends-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=product-sustainability-2-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=scs-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

-1.webp?width=370&height=150&name=suite-intro-1142x510-1024x457%20(2)-1.webp)

%20(1)-1.webp?width=370&height=150&name=suite-city-1142x510-1024x457%20(1)%20(1)-1.webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=unlimted-ideas-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=E-Mobility-Sustainability%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Featured_Image_Supermarket-1024x346%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=crt-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=car-1500x500-1024x341%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=featured_image_1%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=brexit-uk-reach-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=trends-survey-2019-1024x341%20(2).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=ipca-web_1-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=trends-2018_1-1500%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=roadmap-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=france-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=L%C3%A4gerdorf-1024x354%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=blockchain-1500x500_new-1024x341%20%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=iso-5001-energy-efficiency-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=header-recipe-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=csm_CW_ebook_HumanRights_2018-03%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=surfing2-1500x500-1024x341%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=iPoint_Blog_LifeCycle_Portfolio_2018-07_EN_1500x50%20(2).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=iPoint-systems_TOP100_Innovator%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=ifu-Hamburg-Team-620x310-1%20(2).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Child-labour-620x310%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Victor-Vladimirov_Blog%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=Rebecca-LeBlanc_Pic%20(2).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=taxes-accounting%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=UN-Global-Compact_w-1024x422%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=EU-CSR-Reporting-Directive-1024x%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Innovation_iPoint_Emerson_Verdan%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=iPoint_Blog_Digital-Circular-Eco%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Involvement-of-different-departe-1%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Titelbild_v11-1%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=Flow_Dave13-1024x495-1%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=ktf_freighter-travel%20(1)%20(1).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=ktf_water-footprinting%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=ktf_eco-indicators%20(2).webp)

%20(1).webp?width=370&height=150&name=ktf_carbon-leakage%20(1)%20(1).webp)

.webp?width=370&height=150&name=ktf_wine_title%20(2).webp)