by Lukas Stumpf, Josef-Peter Schöggl, Rupert J. Baumgartner

The logics of Circular Economy implementation in businesses, as well as barriers towards Circular Economy, were analyzed in a recent study by the Christian-Doppler-Laboratory for Sustainable Product management at University of Graz, Austria.

Circular Economy as multidimensional approach

In contrast to a linear economy that relies on a “take-make-use-dispose” logic, the Circular Economy (CE) has become an increasingly popular concept to keep materials in production loops and minimize the generation of waste. Hence, companies of different sizes and various sectors have started to engage in projects related to the Circular Economy in a multitude of ways that show the applicability of the concept to create viable business solutions, either through reducing material use, reusing or remanufacturing products, or through recycling or recovering materials. At the same time, the current linear system comes with path dependencies and challenges for CE implementation. The logics of both aspects, CE implementation and barriers towards them, were addressed in a recent study by the Christian Doppler Laboratory for Sustainable Product management at University of Graz, Austria, co-funded by iPoint-systems. The study analyzed 131 CE-related business projects which were obtained from a publicly available database, the Circular Economy Industry Platform and were analyzed with quantitative and qualitative research methods (detailed information on the research methods is available in the research paper).

The Circular Economy in practice

The results of the analysis can be explored interactively via the following link: https://kumu.io/lukasstumpf/131-cases?settings=0.

The analysis covered projects from 21 sectors, with waste management (24 projects), textiles, apparel and leather (22), and plastics and rubber (16) being the most frequent ones. Here, 94 projects were assigned to a single sector, while the remaining 37 were assigned to two, or up to a maximum of four, different sectors. Within all projects, and among all R principles (recycle, recover, reduce, reuse, remanufacture, redesign), recycling was the most dominant R principle (85 projects, ~65% of all cases). In general, both open and closed loop recycling projects were found. At the same time, a considerable importance of recovery of different kinds (materials as well as substances) (46, ~35%) was found in the sample. Implementation of the remaining four principles was comparatively less extensive in the sample.

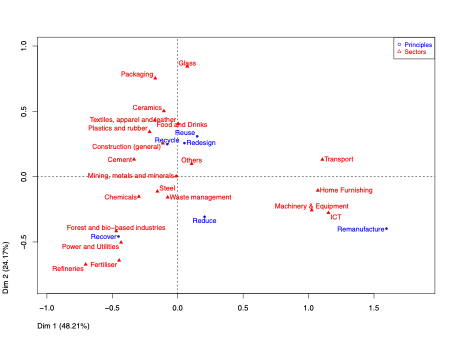

The correlation between the use of CE principles and sectors can be seen in Figure 1. Thereby, three different clusters can be identified:

- Manufacturing and slow-moving goods (transport, home furnishing, machinery equipment, ICT): show a strong relation to remanufacturing, which is a strong distinguishing factor.

- Fast-moving consumer goods and construction (glass, packaging, ceramics, food and drinks, textiles, apparel and leather, plastics and rubber, construction, cement, others): these are not related to remanufacturing, but rather oriented towards recycling, reduce, or reuse.

- Classic B2B industries (steel, chemicals, waste management, forest and bio-based industries, power and utilities, fertilizer, refineries): these are more closely aligned with recovery than with recycling (or reuse, redesign).

The proximity of the three principles reuse, recycle, and redesign in Figure 1 shows that redesign and and reuse are mainly applied in sectors that also use the principle of recycling – showing a tendency towards multidimensional CE approaches (involving, e.g., several CE principles in an overarching CE approach). This is specifically the case for textiles (mainly combining reuse and recycle) and construction (combining redesign and recycle).

Figure 1: Correspondence analysis for principles and sectors

Barriers to a Circular Economy

The study also identified barriers towards CE application. Most important, three different types of barriers were identified: (i) input-related barriers (such as lack of secondary raw material supply, high costs, technological barriers), (ii) output-related barriers (such as lack of demand, lack of customer awareness, or output quality/quantity), and (iii) regulatory barriers (such as lack of definitions and/or standards, lack of government enforcement and cooperation, or lack of harmonization in EU legislation). The most important regulatory barriers are summarized in Table 1.

| Barrier (#projects) | Sectors (#projects) | Specification |

| Lack of definitions and/or standards (52) | Chemicals (10); Plastics and rubber (8); Waste management (8) |

|

| Lack of government enforcement and cooperation (45) | Absolute: Textiles (13); Chemicals (7); Waste management (7); Relative: Cement (4 of 5); Steel (4 of 6) |

|

| Lack of harmonization in EU legislation (30) | Forest and bio-based industries (6); Plastics and rubber (5); ICT (5) |

|

Summary

To sum up, the study finds that a sector-specific approach towards circular economy is required and that multi-dimensional CE thinking (i.e., application of various R principles and strategic approaches towards circularity) increases business impact towards a CE. Additionally, it shows that regulatory barriers need to be addressed to enable CE application.

Read the full paper

Learn more about the study in this blog post. The full paper, “Climbing up the circularity ladder? – A mixed-methods analysis of circular economy in business practice”, was published in Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 316, 128158 and is available open access here: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128158

.png)